An image of Lady Gaga straddling a recumbent Finn Wittrock in an episode of American Horror Story: Hotel was paused on the screen as Enrique, an analyst for the Parents Television Council, read his straightforward description aloud: “‘The countess and Valentino are shown having sex. She is completely naked except for two star-shaped pasties covering her breasts. She is shown sitting on top of him during sex and her bare butt is shown.’” Quoting the dialogue in his notes, he mumbled quickly, “‘I forgot how good you feel inside me.’”

From his cubicle in the nonprofit’s Los Angeles headquarters, Enrique (who requested that his last name be withheld because the PTC occasionally receives threats) was demonstrating the Entertainment Tracking System, the tool the PTC uses to monitor sex and violence on television. He clicked on the drop-down menu for the former and flatly read off the list of options: “‘Anal, bestiality, anatomical reference, double entendre, erection, fetish.’ Anything that comes up, we have a subtopic for it.”

Categories aren’t limited to sex and violence: Bad language is also logged, and they have “all the variations of the words,” Enrique said, including a category for curse words that are bleeped or muted. “Slang comes up a lot that represents certain curse words but don't actually fall under the traditional curse word. … Frick, frickin’, shizz is said now instead of sh-” — he stuttered — “shit.”

The PTC’s four full-time TV analysts watch, record, and archive all primetime broadcast television — 8 to 11 p.m. Monday through Saturday and 7 to 11 p.m. on Sundays — as well as some cable shows, and track their findings. A dark side room in their slick skyscraper office houses huge stacks of DVRs and servers. Another room is taken up by dozens of boxes of VHS tapes of TV shows from their pre-digital days, which represent about half of a catalogued library that comprises tens of thousands of hours of footage, all in the effort to track television’s moral transgressions

“Howard Stern once referred to us as some organization which is an angry mom and a notepad,” Tim Winter, president of the PTC, told BuzzFeed News from their headquarters. “It’s like, ‘No, it’s more than an angry mom with a notepad.’”

But many have accused the PTC of worse. At a 2014 press conference, Stern actually referred to the PTC as “some guy sitting in his basement calling [himself the] Parent Television Council” and proposed that it was “a money-raising racket.” In 2013, Family Guy creator Seth MacFarlane told The Advocate that the PTC was made up of “literally terrible human beings” and likened them to Adolf Hitler. “They can all suck my dick as far as I’m concerned,” he concluded. In 2007, Time critic James Poniewozik dismissed them as “decency bean counters,” and in 1997, Brian Lambert wrote in his column in the St. Paul Pioneer Press that they were no regular watchdogs but rather “strange-looking curs with specks of foam at the corners of their mouths.”

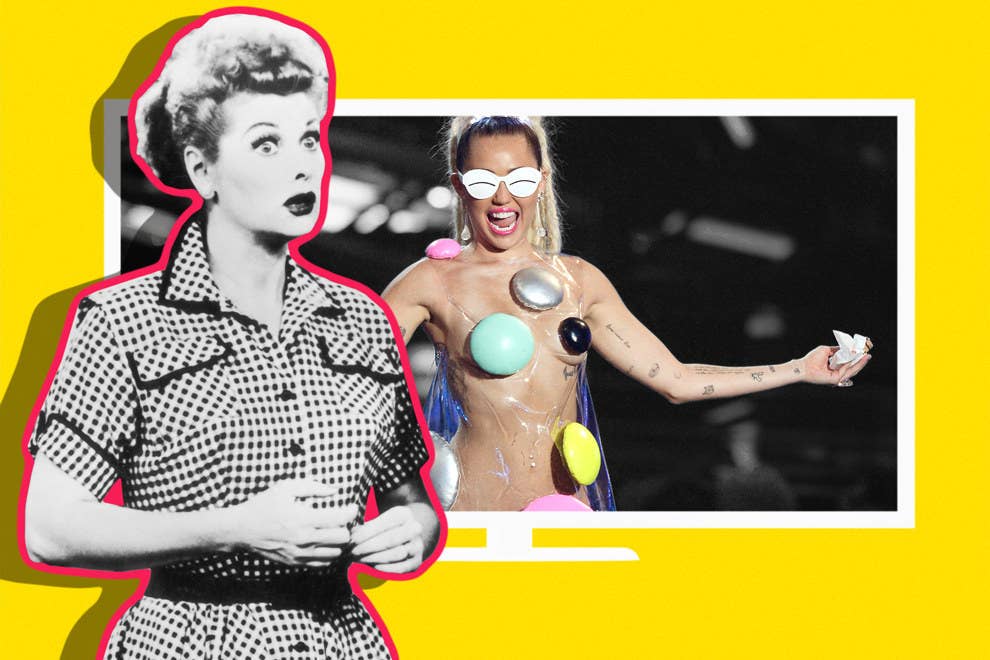

The council inspires these comments by advocating for less sex, violence, and profanity on TV. Their work includes monitoring and analysis for their own regularly released studies, lobbying the Federal Communications Commission and advertisers, and helping dismayed viewers file their own complaints. In the 1990s, they advocated for the voluntary reinstatement of the Family Hour, a short-lived television “child-safety zone” policy that a federal court had already struck down in 1976. Another of the council’s initial objectives was a return to the moral model of television in the ’50s, a decade when standards were so prim that I Love Lucy’s eponymous star was famously described as “expecting” in order to avoid the salacious connotations of “pregnant.” In the expanded media landscape of 2016, where hardcore pornography has never been easier to find by sheer accident, it can be hard to fathom what an organization like the PTC has to offer, and even how an organization like the PTC continues to exist.

But as one of the last holdouts of the ’90s propriety wars, they are in an arguably plum position: "Whenever somebody rips off their blouse, the media calls us and says, 'What do you think, PTC?'" said Winter. With no marketing budget, the council relies almost entirely on "earned media" and its mailing list for donations, and as one of the few groups that's reliably aghast at Miley Cyrus's pelvic gyrations or a condom commercial being aired on a show rated as appropriate for 14-year-olds, they’ve carved out a nice niche for themselves and their revulsions. Their work can seem irrelevant, but that isn't how they see it.

“Are we going to eliminate the world’s appetite for pornographic material? No,” Winter said — however, television is still a favorite medium for children, and Nielsen reported in 2015 that nearly all 2- to 17-year-old Americans watch more than 20 hours a week. “If we can try to make it a safer place for them, we're doing our job,” he said. Thus, they focus on goading their way to small victories — some of which they can claim only dubious credit for — in a battle that’s already been lost. It’s an endeavor so moral that even failure is a triumph.

In the 1990s, the harmful effects of violence in media was a fashionable topic — in 1995’s Clueless, Cher Horowitz delivers a speech that concludes (perhaps presciently) that the attorney general’s resistance to it has “no point.” The PTC was established five years after the Children’s Television Act of 1990 highlighted concern over advertising to children. Although it has long called itself nonpartisan, its strategies were pioneered by its inflammatory ultra-conservative founder and former president, L. Brent Bozell III, who created the council as the “Hollywood project” of the Media Research Center. With an early figurehead in known Democrat Steve Allen, the PTC positioned itself as an impartial commonsense effort, even as Bozell decried Dawson’s Creek’s gay character in the New York Daily News as part of “an agenda in Hollywood to advance the cause of homosexuality as normal behavior.”

The group debuted in time for the debate over the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which laid the groundwork for television ratings and the V-chip, a technology that would work in tandem with ratings to block certain shows from TVs. It was a time when “the whole country recognized that media violence and harmful media content” warranted a response, said Dale Kunkel, a professor emeritus of communication at the University of Arizona and an author of the National Television Violence Study.

The potential dangers of violence in media were, indeed, widely recognized. In 1999, just five weeks after the Columbine High School massacre left 14 teenagers and one teacher dead, President Bill Clinton publicly called on “the entertainment industry” to do its part: “Anyone who doubts the impact of the cultural assault can look at what now, over 30 years, amounts to somewhere over 300 studies, all of whom show that there is a link between sustained exposure … to violent entertainment and violent behavior.” That willingness to place some blame for the school shooting on TV, movies, and music eventually prompted Marilyn Manson to write a defense of his work in Rolling Stone, pointing out that, contrary to reports, the teenage shooters were not even fans of his music.

But the eagerness has certainly faded: In the nearly 20 years that’ve passed, the V-chip has been formally recognized by Congress as a failure — one study found that only 8% of parents used it, and another found that less than half of parents even knew their television had a V-chip. Since the ratings system was implemented, the PTC says it is constantly abused by networks, which have virtually no outside oversight in separating the TV-MAs from the TV-14s.

Even the will to regulate in the first place has waned. The FCC’s indecency practices were challenged repeatedly by the courts in a series of lawsuits triggered by the fine levied for the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show — you may recall Justin Timberlake’s butterfingers denuding Janet Jackson’s nipple. After the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012, President Barack Obama did call somewhat quietly for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to look into media violence, among other things, but most of the president’s plan for preventing the violent deaths of more children was “common-sense gun safety measures.”

From the would-be watershed of Columbine to today, the council has seen other setbacks. It took a financial blow that started with the economic downturn in 2007: In 2006, it drew $5.2 million in donations, and in 2013, it received $3.2 million, according to tax filings. Its donor base is so censorious that some swore never to donate to the group again after the council sent them a mailer containing a photograph of a sparsely clothed Cyrus taken at the 2015 VMAs. Because of cutbacks, the PTC now has 16 employees, less than half the number it had in 2008. But with an annual income that has evened out post-recession, the PTC shows no clear signs of flagging.

Winter, who moved from his executive director role to the presidency in 2006, is obstinate as well: For him, this fight has always been personal. He recounted an origin story he’s been telling the press for more than a decade: He witnessed his then 4-year-old daughter watching a reality show in which a man was licking whipped cream off a woman’s pixelated but otherwise bare breasts. In 2003, in the first public version of this anecdote that BuzzFeed News found, Indiana’s South Bend Tribune reported that Winter was sitting in the room with her, flipping through the channels. He retold it this time with an added layer of helplessness and shock: Winter said he was in the next room dutifully preparing dinner for his child, who — because he could not react immediately — spent that much more time looking at nudity and dairy toppings. A photograph of her as a teenager, wearing white and smiling, sits in a silver frame on his desk as a reminder of why this is all so important to him, why the fight must continue. His is a genesis story for the ages, of sex, innocence, inspiration, and righteous fury.

“You do what you do as a parent,” he said. “You grab the remote and you change the channel. And you hope that innocence hasn't been lost.”

In the PTC’s pro-innocence crusade, much of their ammunition has been data. According to recent tax filings, nearly half of their total funds goes toward logging the content of TV shows and producing studies. Their other main pursuits are more vague: One filing lists “provid[ing] a voice” and facilitating the airing of viewers’ grievances — some of this includes mass mailings to their member base and urging people to file complaints with the FCC. They lobby to “unbundle” cable, so that consumers can choose which channels they want to buy. Another effort is their “Advertiser Accountability” program, which pressures advertisers to stop buying commercial airtime on shows the PTC considers objectionable. Melissa Henson, who runs the program, spends many of her days calling, emailing, and tweeting at companies who advertise during graphic programs. Sometimes the council’s tactics are even more aggressive — occasionally they’ll show up at shareholder meetings (“If there's explicit content [on shows they advertise with], we'll describe it,” Winter said with significance).

The problem with most of the PTC’s activities is that they’re difficult to quantify, much like the effect of television on children, and asserting concrete effects on children has proved to be a liability in the past. In 1999, the council set its sights on the World Wrestling Federation (now World Wrestling Entertainment) after a 6-year-old child was killed by a 12-year-old, seizing on an argument made by the killer’s attorney that his young client was mimicking wrestling moves from shows including WWF’s Smackdown. The PTC blamed the WWF directly for the death of the child, and the WWF successfully sued the PTC for defamation, requiring Bozell and the PTC to publicly apologize to the organization for spreading false information. They also had to apologize for misrepresenting the number of advertisers that had pledged not to buy airtime during the show. The 2002 settlement cost the council $3.5 million — a trolling attempt gone slanderously wrong.

Winter, who joined the PTC after that settlement, said, “What we learned from it is, we had to be very careful in saying that because of X television program, Y consequence in real life happened. I can't say that because of one episode of a show somebody went off and then offed a little kid. We don't tie a specific show to a specific consequence.” Their purpose, in other words, became ever more hazy — they raged against a perpetually nebulous threat.

Likewise, Winter was careful not to claim any specific success for the PTC. He said that many of the shows the PTC had “gone after” in 2015 have been canceled — Hannibal, Sex Box, and Wicked City among them — but he could not say for certain what, if anything, the PTC had contributed to networks’ decisions. He mentioned a council report from summer 2015 that showed Family Guy aired 23 scenes containing sexual violence, 21 of which were played for laughs. “After we published the data on the Family Guy stuff, this season to date, guess how many jokes there have been about sexual assault?” He held up his hand in a zero. “Now, I don't know if it was because of us for sure. But I know the conversations we had, and I know the data we published, and the earned media we received around it, and I hope, I hope, that we were a lever,” Winter said. (Of course, opposition to rape jokes is likely a more palatable position to a wider swath of TV watchers than opposition to the word “frick.”) A representative for Family Guy and a representative for the show’s creator, Seth MacFarlane, did not respond to requests for comment.

Ultimately, their watchdog agenda, which Winter calls “pure,” is so lofty that they rarely need to show actual results. Expectations are low: “We don't feed people, we don't clothe them, we don't house them, we don't give them medical care, we don't give them schools like most other charities. But we're still a charity,” Winter said. “All those things are really important — feeding, clothing, housing, medical, schooling — but if we're not doing our job right, those things matter less. It doesn't matter as much that you give a kid a meal, a house, and a schoolbook if he is consuming entertainment media that is impacting his future behavior, his or her behavior, in a way that they're going to be a less productive, or a less social, citizen. … We're not preventing their nutritional starvation, but hopefully emotionally we're helping them to develop into a more solid citizen.”

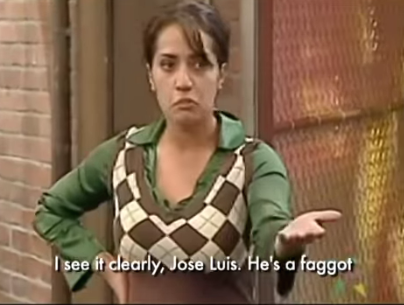

The core tenets of the PTC — that graphic sex and violence on television are bad for children according to science, so we should try to cut down on that — seem neither controversial nor inherently conservative, and yet they can’t seem to escape their past. José Luis Sin Censura was an EstrellaTV broadcast talk show that, before it was canceled in 2012, featured gay slurs that were met with applause supplied by its studio audience. Winter said he and Jarrett Barrios, GLAAD’s president at the time, discussed the PTC joining the LGBT advocacy group in its campaign against the show, and co-signing their complaint to the FCC. But “they felt they weren't ready to stand up with us in public,” Winter said.

Winter claims that the PTC continued campaigning against the show separately from GLAAD (there are currently no mentions of the show on the PTC’s website). Barrios told BuzzFeed News that the FCC complaint was the work of a coalition led by GLAAD and the National Hispanic Media Coalition. “During that period, we were aggressive at soliciting partners with a record of commitment on these issues, and we really embraced as many different groups as we could,” he said diplomatically.

GLAAD and NHMC’s appeal to the FCC was ultimately successful: In 2013, it resulted in a $110,000 fine as part of a settlement in the commission’s first indecency action since 2010 (the Supreme Court warned that their indecency rules were too vague in 2012). The investigation was a signal of changing mores: “Gay slurs” were not particularly high on the public agenda in the ’90s, but offense is subject to fashion, too. Because it has always been behind the times, the PTC was deflected by its would-be partners, then outmaneuvered on its own castigatory turf.

Racial and gender diversity have also been hot topics in criticizing television media, an undercurrent that has not escaped Winter’s attention. The PTC’s assertion that violence and graphic sex on television are bad for children stems from the view that TV has the power to influence the way viewers behave in the world. After all, they point out, TV programming is supported by commercials, which operate on the assumption that media content has the ability to impact real-world choices. “Look at any minority community about how they're depicted on television, and how fierce they are in terms of making sure that there aren't unfair negative portrayals, because they know it has an impact,” Winter said. But when asked whether he sees the PTC as being aligned with organizations calling for more race and gender representation on television, Winter sighed. “Those issues are outside the scope of the PTC mission.”

Though it may be losing ground to progressive television advocacy causes, the PTC has sworn to continue agitating (their 2014 annual report framed their “battles” as “David-versus-Goliath”). That, really, is the whole point of the operation: It is a lost cause, but a lost cause that hovers on the edge of reasonable. So why not keep agitating against the harmful effects of media violence and telling people that your little daughter once briefly saw a man licking whipped cream off a woman’s breast before you could change the channel? On the one hand, 20 years of the PTC failing has demonstrated that it’s too much to ask Hollywood to rein it in, but on the other hand, it’s not much to ask. There is even a tacit acknowledgment at the council that they’ve lost, that all the commotion is an end in itself: During a phone interview with the chair of the PTC’s board, Michele D’Amour, BuzzFeed News asked whether she felt generally positive or generally negative about the direction of television. She laughed, then said, “That’s a loaded question.” TV, according to D’Amour, is on “a fast trajectory into nothing that is worth watching. ... I hope, I pray, the tide is changing.”

CORRECTION

The family hour was struck down by a federal court. An earlier version of this story said it was the Supreme Court.